Wholeness is not truly whole until it is all-inclusive.

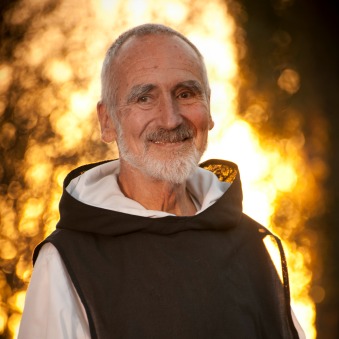

In this essay, Br. David Steindl-Rast reflects on how we make ourselves whole by making each other whole. He explores the Ten Oxherding Pictures in Zen; you might accompany Br. David’s words with the images found alongside Martine Batchelor’s description of the series. ~ Editor’s Note

Wholeness has intrigued me ever since we boys built sand castles on the beach. You built a perfect world. You surrounded it with a moat. You looked up, and there was some incongruous beach chair, a blanket, or simply somebody’s leg, out of scale and totally out of context. No way to bring this out-of-bounds reality into your wholeness. So I learned the lesson early on: Wholeness is not truly whole until it is all-inclusive.

Later, this insight gave me a key to the Ten Oxherding Pictures in Zen; to the last two of them, to be precise. Up to number eight all is clear. Oxherding is a misnomer. But when we know that the series depicts the taming of a wild buffalo, the first seven frames make sense. And once we realize that this metaphor stands for the path to inner wholeness, number eight falls into place, too. What could express wholeness better than this circle, perfect and perfectly empty?

As long as this question remains merely rhetorical, the series ends there. And for a long time it did so, I am told. Then someone raised the question in earnest. Is there a wholeness that goes beyond the point where the Buddha enters nirvana? The answer took shape in the Bodhisattva, who at this point turns and vows not to enter, but to labor till the last of all beings has reached nirvana.

The great death is revealed as life, the great emptiness as fullness.

Now, two more frames were added to the series. Number nine shows the other side, as it were, of number eight: The empty circle is filled. In no other frame does the imagery vary more widely. But the meaning is always exuberant fullness. In my favorite version the circle holds an abundance of blossoms. The great death is revealed as life, the great emptiness as fullness. The final frame shows the Bodhisattva in the market place. A beggar with beggars, with fishmongers, with whores: the one who realized our original wholeness feasting and belly-laughing with out-casts. (“A friend of sinners,” they called Jesus.)

How different, this all-embracing wholeness of the Boddhisattva from the hero who finds wholeness by passing through hell and then lives happily ever after! But is this really what the hero myth tells? Where the myth remains intact, the hero returns to a community, returns as bringer of life for many. Only in a classic Western does he ride off into the sunset, alone. (Any anthropologist will wonder what warped culture produced so warped a version of the hero myth.)

Rilke uncovers wholeness even in the violent end of Orpheus. Did the maenads in their madness tear him limb from limb? They distributed him, Rilke claims, as bread is broken and distributed: a holy communion. Scattered, he keeps singing in every song that sounds. “Take, eat, this is my body given for you.” But eating of this bread takes courage, courage to become in one’s own turn bread for the world.

No wonder Jesus asks before he heals, “Do you want to be made whole?” We know the price of wholeness. Are we willing to become bread in a world where each new sunrise sees the corpses of 50,000 starved children? Wholeness must be all embracing. Do you want to become whole?

Originally published in Parabola:

Vol. 10, #1, Spring 1985, pp. 94-95.

Comments are now closed on this page. We invite you to join the conversation in our new community space. We hope to see you there!