When I remember my last visit with Thomas Merton I see him standing in the forest, listening to the rain. Much later, when he began to talk, he was not breaking the silence, he was letting it come to word. And he continued to listen. “Talking is not the principal thing” he said.

A handful of men and women searching for ways of renewal in religious life, we had gone to meet him in California as he was leaving for the East, and we had asked him to speak to us on prayer. But he insisted that “Nothing that anyone says will be that important. The great thing is prayer. Prayer itself. If you want a life of prayer, the way to get to it is by praying.

“As you know, I have been living as a sort of hermit. And now I have been out of that atmosphere for about three or four weeks, and talking a lot, and I get the feeling that so much talking goes on that is utterly useless. Something has been said perfectly well in five minutes and then you spend the next five hours saying the same thing over and over again. But here you do not have to feel that much needs to be said. We already know a great deal about it all. Now we need to grasp it.

In prayer we discover what we already have. You start where you are and you deepen what you already have, and you realize that you are already there.

“The most important thing is that we are here, at this place, in a home of prayer. There is here a true and authentic realization of the Cistercian spirit, an atmosphere of prayer. Enjoy this. Drink it all in. Everything, the redwood forests, the sea, the sky, the waves, the birds, the sea-lions. It is in all this that you will find your answers. Here is where everything connects.” (The idea of “connection” was charged with mysterious significance for Thomas Merton.)

Three sides of the chapel were concrete block walls. The fourth wall, all glass, opened on a small clearing surrounded by redwood trees, so tall that even this high window limited the view of the nearby trees to the mammoth columns of their trunks. The branches above could only be guessed from the way in which they were filtering shafts of sunlight down onto the forest floor. Yes, even the natural setting of Our Lady of the Redwoods provided an atmosphere of prayer, to say nothing of the women who pray there and of their charismatic abbess. On the day we had listened to the Gospel of the Great Wedding Feast, flying ants began to swarm all across the forest clearing just as the communion procession began, tens of thousands of glittering wings in a wedding procession. Everything “connected.”

To start where you are and to become aware of the connections, that was Thomas Merton’s approach to prayer. “We were indoctrinated so much into means and ends,” he said, “that we don’t realize that there is a different dimension in the life of prayer. In technology you have this horizontal progress, where you must start at one point and move to another and then another. But that is not the way to build a life of prayer. In prayer we discover what we already have. You start where you are and you deepen what you already have, and you realize that you are already there. We already have everything, but we don’t know it and we don’t experience it. Everything has been given to us in Christ. All we need is to experience what we already possess.

We are sharecroppers of time. We are threatened by a chain reaction: overwork–overstimulation–overcompensation–overkill.

”The trouble is, we aren’t taking time to do so.” The idea of taking time to experience, to savor, to let life fully come to itself in us, was a key idea in Thomas Merton’s reflections on prayer. “If we really want prayer, we’ll have to give it time. We must slow down to a human tempo and we’ll begin to have time to listen. And as soon as we listen to what’s going on, things will begin to take shape by themselves. But for this we have to experience time in a new way.

“One of the best things for me when I went to the hermitage was being attentive to the times of the day: when the birds began to sing, and the deer came out of the morning fog, and the sun came up – while in the monastery, summer or winter, Lauds is at the same hour. The reason why we don’t take time is a feeling that we have to keep moving. This is a real sickness. Today time is commodity, and for each one of us time is mortgaged. We experience time as unlimited indebtedness. We are sharecroppers of time. We are threatened by a chain reaction: overwork–overstimulation–overcompensation–overkill.

“We must approach the whole idea of time in a new way. We are free to love. And you must get free from all imaginary claims. We live in the fullness of time. Every moment is God’s own good time, his kairos. The whole thing boils down to giving ourselves in prayer a chance to realize that we have what we seek. We don’t have to rush after it. It is there all the time, and if we give it time it will make itself known to us.”

In contrast to the person whose time is mortgaged, the monk is to “feel free to do nothing, without feeling guilty.” All this reminded me of Suzuki Roshi, the Buddhist abbot of Tassajara, who had said that a Zen student must learn “to waste time conscientiously.” I was not surprised, then, to hear Thomas Merton refer explicitly to Zen in this connection. “This is what the Zen people do. They give a great deal of time to doing whatever they need to do. That’s what we have to learn when it comes to prayer. We have to give it time.” There is, in all this, a sense of the unfolding mystery in time, a reverence for gradual growth.

‘One of the greatest obstacles to your growing is the fear of making a fool of yourself. Any real step forward implies the risk of failure. And the really important steps imply the risk of complete failure.’

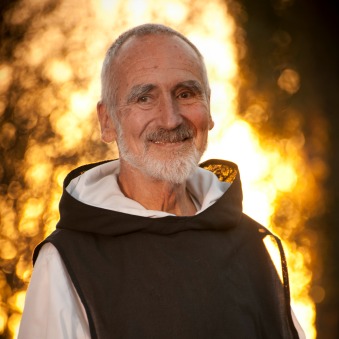

We were sitting in front of a blazing fire when Thomas Merton again took up this theme of growing. “The main theme of time is that of inner growth. It’s a theme to which we should all return frequently in prayer. There is a great thing in my life – Christ wants me to grow. Move this around a little bit in meditation. Instead of worrying – Where am I going? What kind of resolution should I make? – I should simply let this growing unfold in my prayer. I should see what is holding me back from it. What is it? What kind of compromises have I made? Am I substituting activity for growth? (I have often asked myself, is this writing getting in the way? For me writing is so satisfying an activity that it is hard to say.) In someone else it is easier to see this process of growing and to see what hinders it. But when it comes to ourselves, all we can do is try to honestly be ourselves.

“One of the greatest obstacles to your growing is the fear of making a fool of yourself. Any real step forward implies the risk of failure. And the really important steps imply the risk of complete failure. Yet we must make them, trusting in Christ. If I take this step, everything I have done so far might go down the drain. In a situation like that we need a shot of Buddhist mentality. Then we see, down what drain? So what? (So that’s perhaps one of the valuable things about this Asian trip.) We have to have the courage to make fools of ourselves, and at the same time be awfully careful not to make fools of ourselves.

“The great temptation is to fear going it alone, wanting to be ‘with it’ at any cost. But each one of us has to be able to go it alone somehow. You don’t want to repudiate the community, but you have to go it alone at times. If the community is made up of a little group of people who always try to support one another, and nobody ever gets out of this little block, nothing happens and all growth is being stifled. This is possibly one of the greatest dangers we face in the future, because we are getting more and more to be that kind of society. We will need those who have the courage to do the opposite of everybody else. If you have this courage you will effect change. Of course they will say, ‘this guy is crazy’; but you have to do it.

“We are too much dominated by public opinion. We are always asking, what is someone else going to think about it? There is a whole ‘contemplative mystique,’ a standard which other people have set up for you. They call you a contemplative or a hermit, and then they demand that you conform to the image they have in mind. But the real contemplative standard is to have no standard, to be just yourself. That’s what God is asking of us, to be ourselves. If you are ready to say ‘I’m going to do my own thing, it doesn’t matter what kind of a press I get,’ if you are ready to be yourself, you are not going to fit anybody else’s mystique.”

Again and again I was amazed to find him at once so totally uninhibited and so perfectly disciplined.

He himself certainly didn’t. When I saw him for the first time at the Abbey of Gethsemani he was wearing his overalls and I thought he was the milk delivery man. He wasn’t going to fit my mystique either. Two other faces came to mind whenever I looked at his features, Dorothy Day and Picasso. When the chapel was getting dark and he bent down to hear confessions, there was more of Dorothy Day. When he read poetry (his own reluctantly, but his friends’ poems with relish) there was more of Picasso. Again and again I was amazed to find him at once so totally uninhibited and so perfectly disciplined.

He saw the wrong kind of self-fulfillment as one of our great temptations today. “The wrong idea of personal fulfillment is promoted by commercialism. They try to sell things which none of us would buy in our right mind; so they keep us in our wrong mind. There is a kind of self-fulfillment that fulfils nothing but your illusory self. What truly matters is not how to get the most out of life, but how to recollect yourself so that you can fully give yourself.” Self-acceptance, sober and realistic, was basic in Thomas Merton’s view.

“The desert becomes a paradise when it is accepted as desert. The desert can never be anything but a desert if we are trying to escape it. But once we fully accept it in union with the passion of Christ, it becomes a paradise. This is a great theological point: any attempt to renew the contemplative life is going to have to include this element of sacrifice, uncompromising sacrifice. There is no way around it if we want a valid renewal.

‘The danger is that the institution becomes an end in itself. What we need are people-centered communities, not institution-centered ones. This is the direction in which renewal must move.’

“It’s all a matter of rethinking the identity of institutions so that everything is oriented to people. The institution must serve the development of the individual person. And once you’ve got fully developed people, they can do anything. What counts are people and their vocations, not structures and ideas. Let us make room for idiosyncrasies. The danger is that the institution becomes an end in itself. What we need are people-centered communities, not institution-centered ones. This is the direction in which renewal must move.

“Maybe new structures are not that necessary. Perhaps you already do know what you want. I believe that what we want to do is to pray. After all, why did any of us become religious if we didn’t want to pray? What do we want, if not to pray? Okay, now, pray. This is the whole doctrine of prayer in the Rule of St. Benedict. It’s all summed up in one phrase: ‘If a man wants to pray, let him go and pray.’ That is all St. Benedict feels it is necessary to say about the subject. He doesn’t’ say, let us go in and start with a little introductory prayer, etc, etc. If you want to pray, pray.

“Now that all the barriers are taken away and the obstacles gone and we find ourselves with the opportunity to do whatever we want, we see the real problem. It is in ourselves. What is wrong with us? What is keeping us back from living lives of prayer? Perhaps we don’t really want to pray. This is the thing we have to face. Before this we took it for granted that we were totally dedicated to this desire for prayer. Somebody else was stopping us. The thing that was stopping us was the structure. Now we simply find that maybe a structure helps. If some of the old structure helps, keep it. We don’t have to have this mania for throwing out structures simply because they are structures. What we have to do is to discover what is useful to us. We can then discard structures that don’t help, and keep structures that do help. And if it turns out that something medieval helps, keep it. Whether it is medieval or not, doesn’t matter. What does matter is that it helps you become yourself, that it helps you live a life of prayer.

“It’s a risky thing to pray, and the danger is that our very prayers get between God and us. The great thing in prayer is not to pray, but to go directly to God. If saying your prayers is an obstacle to prayer, cut it out. The best way to pray is: stop. Let prayer pray within you, whether you know it or not. This means a deep awareness of our true inner identity. It implies a life of faith, but also of doubt. You can’t have faith without doubt. Give up the business of suppressing doubt. Doubt and faith are two sides of the same thing. Faith will grow out of doubt, the real doubt. We don’t pray right because we evade doubt. And we evade it by regularity and by activism. It is in these two ways that we create a false identity, and these are also the two ways by which we justify the self-perpetuation of our institutions.

‘We need a theology of liberation instead of an official debt machine.’

“But the point is that we need not justify ourselves. By grace we are no longer under judgment. I must remember both that I am not condemned, yet worthy of condemnation. How can I live the message of Christian newness in these final days? I am not called to gather merit, but to go all over the world taking away people’s debts. (This is not the prerogative of a priestly caste.) We need a theology of liberation instead of an official debt machine. I belong entirely to Christ. There is no self to justify.”

There were so many points of contact with Zen Buddhist teaching in all this that I couldn’t help asking whether he thought he could have come to these insights if he had never come across Zen. “I’m not sure,” he answered pensively, “but I don’t think so. I see no contradiction between Buddhism and Christianity. The future of Zen is in the West. I intend to become as good a Buddhist as I can.”

And yet, Thomas Merton’s Christian faith wasn’t watered down to the point where it would become compatible with most anything. It was throbbing with life. This came out most clearly in little personal remarks, for example in what he said about so traditional a theme as prayer of intercession. “It’s simply a need for me to express my love by praying for my friends; it’s like embracing them. If you love another person, it’s God’s love being realized. One and the same love is reaching your friend through you, and you through your friend.”

“But isn’t there still an implicit dualism in all this?” I asked. His answer was, “Really there isn’t, and yet there is. You have to see your will and God’s will dualistically for a long time. You have to experience duality for a long time until you see it’s not there. In this respect I am a Hindu. Ramakrishna has the solution. Don’t consider dualistic prayer on a lower level. The lower is higher. There are no levels. Any moment you can break through to the underlying unity which is God’s gift in Christ. In the end, Praise praises. Thanksgiving gives thanks. Jesus prays. Openness is all.” He was ready to go to Bangkok.

Excerpted from Monastic Studies (Mount Saviour Monastery, Pine City, NY; 1969). Before leaving for the East – and his death on December 10, 1968, in Bangkok – Thomas Merton attended a meeting of Our Lady of the Redwoods Abbey in Whitethorn, California. The preceding notes by Brother David were made there.

Comments are now closed on this page. We invite you to join the conversation in our new community space. We hope to see you there!